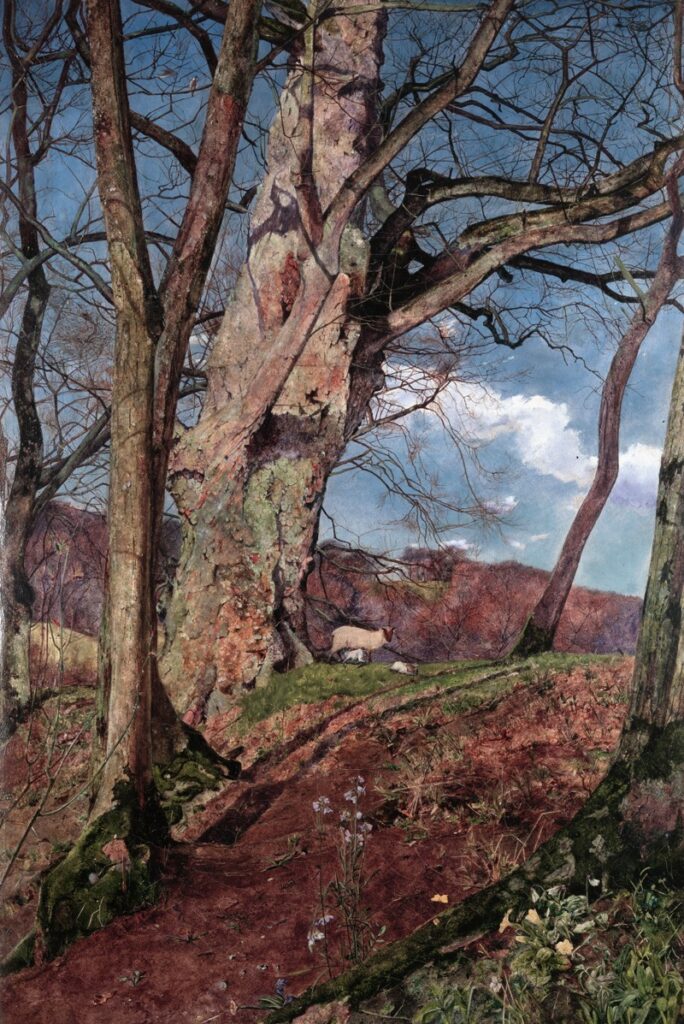

And so we have a painting, which – while not traditionally religious – nevertheless feels like a work of faith, a spiritual revelation. At one level, A Study, in March is just an image of an odd corner of the English landscape in early spring, that time when the branches are still bare, but little flowers, bright skies, brisk sunny days, and the arrival of lambs promise an end to winter. The lambs are just lambs – not the Lamb of God. But surely there is a suggestion here that – if we turn a contemplative eye on this quietly regenerating landscape – if we look carefully and faithfully at the humble details of flower and tree, field and sky, we will see signs of God. Perhaps , this Lent, we may need to bend down low and look in humble, ordinary places, the sort of places we go for an afternoon walk during lockdown. This is not about climbing mountains and gazing commandingly from dizzying heights at deep valleys. It is about reconnecting with the earth from which we are made (Genesis 2:7), and learning to look well – as well as to look up. If we do this, perhaps we will see the sheep and her two lambs for what they are, the common miracle of birth and love, the work of God’s Holy Spirit in everyday things. I’m reminded of the insight of Gerard Manley Hopkins in his 1877 poem, ‘God’s Grandeur’, that despite all the troubles of life and the environmental woes we have made for ourselves, ‘nature is never spent/there lives the dearest freshness deep down things’.

John William Inchbold (1830-1888) was born and died in Yorkshire, but spent most of his life travelling: in Christopher Newall’s words, he was a ‘rootless and peripatetic individual who painted many landscapes in different parts of Europe in his lifetime’ (Victorian Watercolours, p. 76). But this oil painting – A Study, in March (1855) – feels like the work of an artist who was deeply drawn to his native landscape, and quite literally close to the soil. We seem to be sitting in a low ditch with Inchbold as he paints, looking up a path worn by livestock between two fields. Inchbold has broken some of the traditional rules of composition for landscape painting – the intensely detailed foreground takes up more than a third of the image, and our view of the middle distance is cut off by the low angle of the perspective. We look up to the sheep in the field from our quirky viewpoint, and our attention is drawn to the wildlife immediately at our feet – the primroses peeping through on the right, the yellow butterfly settled near them, and the harebells at the bottom centre of the image. It is generally held that the image was inspired by lines from William Wordsworth’s great poem, The Excursion: ‘When on its sunny bank the primrose flower/ peeped forth to give an earnest of the Spring …’. Spring is further evidenced by the sheep with her two lambs, one of whom is busy feeding on her milk.

Our eyes are drawn to the little details of the flowers, of the gnarled and perhaps gnawed bark on the trees, of the wispy grass in the foreground, because of the intense realism of Inchbold’s image, which seems almost photographic in quality. The painter was profoundly influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and its primary promoter, the art critic John Ruskin. Ruskin urged artists to recover the ‘innocent eye’ of the medieval artist, to depict what they saw before them without attempting to re-order it according to the rules of ‘Great Art’, the traditions explained for young British artists in Joshua Reynolds’ Discourses on Art (1769-90). Pre-Raphaelite artists created images in which there was no clear central focus, in which every part of the image was depicted in equally faithful detail, and in which colours were not blended tastefully, but painted in all their bright diversity. Although Ruskin himself eventually lost his childhood Evangelical faith, he believed that painters could reveal the mind of God by painting the created world as God himself had shaped and composed it.

Rosemary Mitchell